Greg Miller·Sunday, June 04, 2023

Will West Coast port labor negotiations devolve into a major, extended disruption to U.S. supply chains, akin to the labor fallout in 2014-2015? If there was a way to place a “prop” bet on this, how have the odds changed since the last port labor contract expired on July 1, 2022?

The longer the talks drag on, the higher the chance of a worst-case scenario. Talks on the new contract began in May 2022. The one-year anniversary has now come and gone.

There have been glimmers of hope along the way, at times nudging the betting line toward a less dramatic climax. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) said on April 20 that agreements were reached “on certain key issues,” reportedly including automation.

Yet some handicappers would have noticed the timing. That announcement came the very day the Biden administration’s pick to lead the Department of Labor, Julie Su, had her Senate nomination hearing. The progress announcement allowed her to tell lawmakers she had obtained positive results after engaging the parties.

Oddsmakers who placed little weight on the April 20 announcement look like they’re right. The betting line just shifted in favor of the large-scale disruption scenario.

West Coast disruptions flare up again

On Friday, the ILWU staged “concerted and disruptive work actions that effectively shut down operations at some marine terminals at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach,” said the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA), the group representing the terminals in the labor negotiations.

The ILWU staged “similar work actions that have shut down or severely impacted operations at the ports of Oakland, Tacoma, Seattle and Hueneme,” said the PMA.

According to Jessica Dankert, vice president of supply chain at the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA), “Retailers are alarmed to learn of the work stoppage underway at several West Coast ports. If this work stoppage drags on and contract negotiations continue to falter, the Biden-Harris administration must step in and broker a deal.”

Negotiations between the union and employers “deteriorated” over wages, with workers not showing up at some terminals beginning Thursday night and extending into Friday, reported the Wall Street Journal.

“Any reports that negotiations have broken down are false,” said ILWU President Willie Adams. He highlighted the health risks and lives lost of ILWU members during COVID and the “astronomical revenues” of ocean carriers during that period, and argued that ILWU members deserve “an economic package” that accounts for their role in the shipping industry’s windfall — in other words, they want a piece of the pandemic profit pie. Adams specifically pointed to the falling percentage of ILWU wages and benefits in comparison to PMA profits.

ILWU Local 13 said, “Ocean carriers and terminal operators have thumbed their noses at the work force’s basic requests, insinuating that the health risks and the loss of lives … during the pandemic did not matter to them and they were expendable in the name of profit.”

In reference to union members not showing up for work on Friday, ILWU Local 13 said “the rank-and-file membership of the Southern California ILWU has taken it upon themselves to voice their displeasure with the ocean carriers’ and terminal operator’s position.”

Second major disruption this year

The latest work slowdown is the second major incident this year, although there also have been multiple smaller and more subtle disruptions, according to the PMA and Agriculture Transportation Coalition.

Work previously stopped in the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach for 24 hours between the night shift on March 30 and day shift on March 31. Terminals were shuttered.

As with the late-March slowdown, U.S. exporters were caught in the middle in Friday’s incident. Export goods turned away from terminals due to labor action need to be stored elsewhere until cargoes can be received, with added storage costs cutting into exporter profit margins. Storage costs for refrigerated food cargoes are even higher.

On the import front, U.S. shippers have already shifted supply chains toward East and Gulf Coast ports in preparation for potential disruptions on the West Coast.

But the U.S. supply chain’s exposure to labor unrest remains acute. The top West Coast ports handled 812,000 twenty-foot equivalent units of containerized import in April, accounting for 48% of the country’s total, according to The McCown Report.

Backup protocols from COVID era still in place

On a positive note, the U.S. supply chain has very recent and in-depth experience dealing with vastly greater congestion than occurred when labor disruptions backed up traffic in 2015.

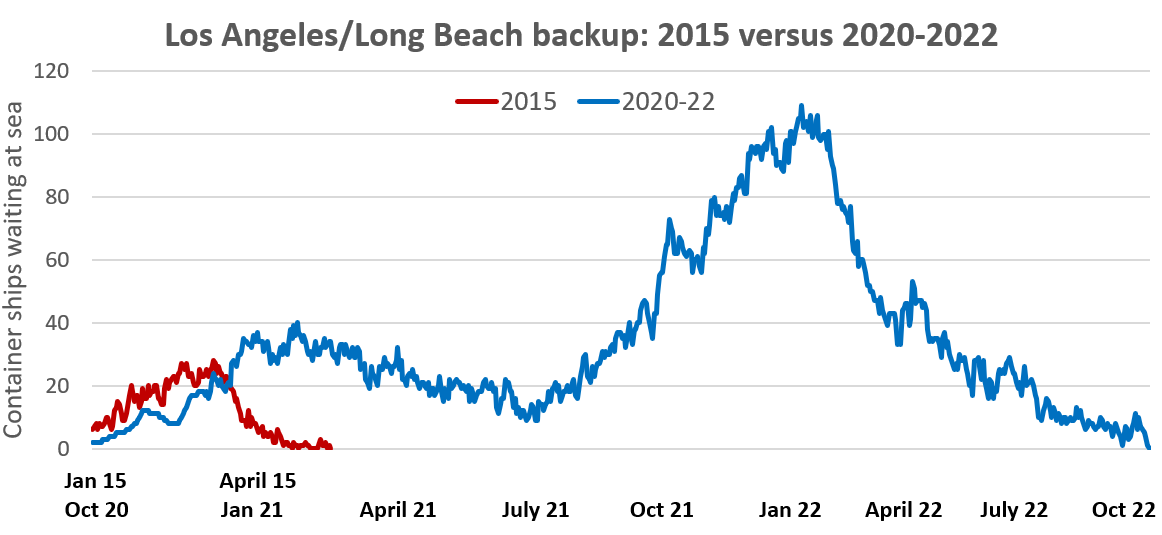

According to data from the Marine Exchange of Southern California, the prior labor contract disruption caused a maximum of 27 ships to wait off Los Angeles/Long Beach amid a backup lasting three months. In the COVID era, the Los Angeles/Long Beach backup peaked at 109 ships and spanned two years.

A system is already in place to deal with labor-related backups courtesy of lessons learned during the COVID-era backup.

“Vessel traffic is still moving per schedules and no schedules have slipped yet, so no backup,” said Kip Louttit, executive director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California, in a report to media on Friday.

“Thankfully, the new queuing system … has remained in effect for the past six months [since the COVID backup ended] even though it was not needed because there was ample labor. If the current labor actions do result in a container vessel backup and berthing dates are slipped back, because partners kept the system going, each vessel has a calculated time of arrival [CTA].

“With CTA in hand and published on the Master Queuing List, if a backup develops, ocean carriers are requested to return to backup protocols … as we did during the 2021-2022 backup,” said Louttit.